Seals General

Seal was a main source of food for many cultures, but particularly for Inuit, Inuvialuit, Yupik and Inupiat [1, 4, 28, 30, 31, 33, 42, 54, 62, 64, 68, 73, 74, 100-103]. The Northern and Central Nootka considered seals a prized food source [122].

Hunting

The seal hunt was primarily carried out in winter and spring, but also to a lesser extent in summer and fall; some cultures hunted all year-round [4, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 28, 29, 33, 43, 44, 46, 49, 58, 62, 67-69, 71, 75, 77, 85, 88, 90, 91, 94, 96, 100, 101, 105, 107-109, 114-117]. The Northern and Central Nootka and Tsimshian hunted year round, but primarily in early spring [122, 130]. The Eyak hunted mainly in summer, while Inuit of Hopedale, Labrador, hunted in late summer/fall [69, 125].

Seal hunting was typically performed by men. This is reported for the Coast Salish, Bella Coola (Nuxalk), Haida, Tsimshian, Inuit, Yupik and Micmac (Mi’kmaq) [2, 3, 13, 14, 29, 38, 43, 67, 79, 118]. During winter, Inuit men left the winter village with sleighs dragged by dogs. They guided themselves towards the hunting grounds using the stars or the direction of wind. Although Inuit men were usually the seal hunters, there are reports of women seal hunters and of women and children participating in the hunt by checking breathing holes [79]. Inuit boys are reported to have watched the dogs while their fathers hunted [67].

Often the seal hunt was conducted in teams. This is reported for Inuit, Passamaquoddy, Coast Salish and Yupik [7, 15, 29, 101, 108].

Seal was hunted in open waters (usually from kayaks), on sandy or rocky shores, and from ice or floe edges depending on the species, region and season [1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 29, 33, 34, 38, 43, 58, 63, 64, 66-69, 71, 77, 79, 80, 85, 86, 88, 90, 91, 94, 100, 101, 108-110, 114-117]. Seal were generally hunted where available according to season: on open waters (usually from canoes or kayaks), on sandy or rocky shores, or on ice [69, 122, 123, 126, 127, 141].

Harpoons/spears, clubs, bows and arrows, nets, and in latter times, rifles were used to hunt seal [1-7, 11-15, 18, 21, 25, 27, 29, 32-34, 38, 43, 44, 49, 51, 56-58, 63, 66-69, 71, 73, 79, 80, 86, 90, 91, 94, 96, 100, 101, 104, 107, 111, 114, 115, 122, 126, 127, 131, 133-136, 139, 141]. Harpoon, and bow and arrow were often used on open water while club was typically used on the shore [69, 122, 126, 127, 131, 139, 141].

Cultures reported to have used harpoon/spear include the Central Coast Salish, Northern and Central Nootka, Kwakiutl, Bella Coola, Haida, Kyuquot, Tlingit, Tanaina and Eyak [1, 69, 122, 126, 127, 131, 133, 135, 136, 139, 141]. Northwest cultures used a variety of harpoons including those with a single or double foreshaft, and those with a detachable or non-detachable head [127]. The Tlingit used harpoons with a detachable barbed head [135, 136]. The Haihais, Bella Bella, and Oowekeeno used harpoons with a detachable head [131]. The Kyuquot traditionally used harpoons, but switched to rifles when they were introduced [134].

The Central Coast Salish, Haida and Tanaina used other tools as well [1, 139, 141]. The Central Coast Salish used nets, and clubs, using clubs when specialized hunters were close enough to the seal [139]. The Tanaina used bow and arrow from kayaks, and used clubs to hunt them on the shore where the tide was low [141]. The Haida used nets, clubs, and bows and arrows to hunt seals that were on shore [1].

Bering Sea–Okvik Neo-Eskimo (Yupik) are thought to have hunted seal with toggle harpoons on floe edges [4]. The Pre-Dorset used harpoons and the Dorset used toggle harpoons [32]. The Birnirk culture hunted them on open water and on ice in Point Barrow and the Northwest Coast [64, 88]. The Thule (pre-Inuit) are thought to have relied on seal during winter when other sources of food were scarce and stored supplies were depleted. They likely hunted on open waters from kayaks using harpoons, and in latter times, threw barbed bladder darts at the seals [34]. Beothuk are thought to have hunted them with harpoons made of antler [44, 111].

Cultures of the Northwest Coast hunted seal from the shore or on open waters from canoes; they used harpoons, and sometimes clubs [80, 86]. The Chinookans of Lower Columbia hunted them with spears or muskets [51]. Coast Salish hunted seal with nets, clubs, or single-pronged harpoons depending on the situation [7, 57]. They used nets made of sinew, and clubs for seals resting on the shore [2, 5]. Sometimes, they hid in sealskin and mimicked the seal’s call in order to get closer. They also hunted in teams of two or three from canoes, taking care to be silent [7]. When hunting in teams of three, they used a three-seated canoe with seats for the steersman, harpooner and float man and used a harpoon to slaughter the seal [5]. The Squamish hunted seal during summer in the evening or early morning, using harpoons [107]. The Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw) hunted seal on open water with a harpoon of a barbed head and a line of cedar bark and sinew; when seals were found resting on the shore, Kwakiutl used clubs [11, 63]. The Bella Coola hunted seal, which was an occasional food source, with nets or bows and arrows [3]. Haida men hid behind screens on shore or encircled seal in open waters with their canoes [1, 38]. They used bows and arrows, clubs, spears and harpoons with cedar shafts and detachable barbed heads made of bone [6, 38]. The People of Port Simpson (Tsimshian) hunted seal with harpoons in spring; in later years, they switched to rifles [96].

The Eyak of the Copper River Delta, Alaska hunted according to season: either in open waters, on sandy or rocky shores or on ice. In summer, they used clubs, or sometimes harpoons to hunt those on the river shore. They also mimicked the seal’s behaviour and cry to lure the mammal [69]. From February to spring they used harpoons on ice [18]. Nunivak Yupik men hunted seal on kayaks or from floe edges during spring. In fall they teamed up in pairs to install nets under the ice. At times, they hunted seals at breathing holes [29]. Inupiat of Northwest Alaska often conducted the seal hunt individually [93]. They used nets anchored with rocks and maintained buoyant with sealskin or bladder floats to catch seal [104]. Nuiqsut (Inupiat) hunted seals in summer on open water using motor boats in more recent times [109].

Inuvialuit (Kigirktarugmiut, Nuvorugmiut and Avvagmiut) are reported to have hunted seal throughout the year employing techniques that suited the season. In winter when food reserves were low and fresh food supplies were scarce, they built snow houses on the ice and harpooned seal through breathing holes. After the ice had broken up, they took to kayaks on open water with nets, harpoons and bows and arrows [4, 33]. This harpoon had a walrus tusk foreshaft and wood shaft, and a float made of sealskin to indicate the seal’s location. At breathing holes, they used a harpoon which did not have a detachable head [94].

Inuit used a harpoon with a head made of antler or walrus tusk and a blade made of bone, stone, or more recently iron. It had a line made of seal thong and a bone pick at the other end to make holes in the ice; the shaft was made of wood or narwhal tusk [68, 79]. Inuit also hunted seals on floe-edges during winter [77]. During spring, they wore sealskin as camouflage and mimicked the seal’s cry to get close to seal basking on the ice [68, 85, 100]. Inuit also used nets to catch seal and in recent times, they used rifles rather than harpoons. When possible, Inuit hunted seal in open waters from kayaks, using a harpoon equipped with a sealskin float [68].

Central Inuit, including Copper, Netsilik and Iglulik, hunted year-round with techniques suited to the season. They are reported to have relied on seal most of the year, but particularly in winter [17, 74, 94]. In winter, they hunted seal at breathing holes, using an unang: a light harpoon with a detachable head, a knob of ivory and a shaft crafted of wood, bone, or ivory, according to availability of materials. They also hunted seal with an agdliaq [71, 91].

Copper and Netsilik Inuit hunted seal at breathing holes in the ice from December to mid-May. They did this at winter camps, where as many as 200 people would gather together, increasing the odds of a catch [15, 17]. Seal breathing holes were typically located by individual community members or by dogs, and seals were slaughtered with a harpoon made of antler and a non-detachable bear bone head [94, 114]. Sometimes hunters attracted seal by imitating seal cries [94, 114]. They also hunted seals on the shore from mid-May to mid-June [15]. In kayaks, Copper and Netsilik Inuit used a harpoon made to be thrown. This harpoon had a walrus tusk foreshaft and wood shaft, and a float made of sealskin to indicate the seal’s location. Caribou Inuit, who rarely hunted seal, hunted them during summer on the coast [94].

Iglulik Inuit hunted seal at their breathing holes from mid-January to the end of April. This was done at winter camps, where 10 to 30 people gathered together, increasing the odds of a catch. They hunted seals on the surface of the ice and by the shore from early April to mid-July, and from mid-July to the end of October; when on the water, teams of two to three men hunted from kayaks with harpoons [15, 94, 116]. Breathing hole hunting continued during the spring, but surface hunting on ice was more frequent [116]. Baffinland Inuit hunted seal at breathing holes or on ice/floe edges during winter using harpoons. Floe edge hunting continued until spring, when they also hunted seal on the ice’s surface. The breathing-hole method was the most widely used during winter, while the surface hunt was efficient during spring [115]. They also hunted seal on open water from kayaks using a throwing harpoon made of a walrus tusk foreshaft and wooden shaft, and a float made of sealskin to indicate the seal’s location [12, 94]. At breathing holes, they used a harpoon which did not have a detachable head [94]. They later traded traditional weapons for rifles [115].

Quebec Inuit men hunted seals on the ice using a specialized harpoon [14]. Beginning in May, Labrador Inuit hunted seal from kayaks using a harpoon with a detachable shaft, which they referred to as a “summer” or “kayak” harpoon. They also used lances made of ivory. During winter until mid-January they hunted seal at breathing holes. Later in winter, they hunted by crawling and mimicking the seals’ cries [58, 94]. The Montagnais (Innu) used clubs [120]. The West Main Cree used harpoons [25]. and Copper Inuit are reported to have targeted basking seals [109, 142], as did Nuiqsut Inupiat in April to May [109].

Micmac males typically teamed up to hunt seals, using harpoons made of a barbed head made of ivory or bone to slaughter them [13]. They used decoys made of wood or moss-stuffed seal skin, wore seal skins and crawled on ice to reach their prey [117]. When the seals were onshore or in coastal waters, they were killed using clubs. On the water, they approached using 24-foot long canoes [43]. The Passamaquoddy teamed up in pairs and hunted from canoes the month of June [108].

Preparation

Many cultures valued seal flesh and some considered it a delicacy [2, 5, 6, 36, 38, 43, 80, 91]. Sharing was reported as important to many cultures [7, 15, 54, 57, 91, 98]. The Micmac and Coast Salish consumed oil during feasts [8, 43, 53]. The Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth) Aht and the Coast Salish shared seals during feasts, and among Inuit, catching a seal was an opportunity for feasting [54, 57, 98]. The Bering Strait Yupik held a feast in fall called the Bladder Festival to honor the sacrifice of the seals [90]. Seal hunting was an important source of food and wealth for the Old Bering Sea – Okvik Neo Eskimo [4]. Seal hunting brought prestige to Inuit and Coast Salish hunters [5, 73]. Coast Salish reserved seal hunting for members of higher rank, and productive seal hunting and seal sharing enabled the hunter to gain a higher status [5, 57]. Among the Coast Salish, the use of nets and clubs to hunt seals that were resting on the shore did not bring as much prestige as other “riskier” techniques [2].

Nearly all parts of the seal were consumed including the flesh, blubber, flippers, organs, blood and fetuses [69, 126-130, 132-134, 140]. When the Kwakiutl butchered seal, they removed the flippers first and kept the blood in a dish. They kept most of the organs except the gall and milt. They cut the blubber in stripes or in a spiral, according to the number of seals available [126].

Seal meat was consumed boiled, broiled, steamed, roasted, smoked, dried fermented, aged, raw-fresh, raw-frozen, and in latter times, fried. Boiling, the most common of preparation methods, used hot stones in a vessel [2, 5, 7, 8, 10, 14, 24, 27, 29, 31, 40, 41, 50, 54, 69, 70, 73, 74, 78, 83, 85, 91, 96, 98, 101, 126, 128, 129, 132, 134].

The Puget Sound culture, Kwakiutl, Eyak, Southeast Alaskan cultures (including Tlingit) and Kyuquot boiled the meat [69, 126, 128, 129, 132, 134]. The Kwakiutl, Tlingit and Eyak used hot stones to boil the meat; the Eyak and Tlingit boiled the meat in spruce baskets, and the Puget Sound culture also boiled it in baskets [69, 126, 128, 129]. The Kwakiutl also steamed seal meat with blubber and skunk cabbage [126]. The Tlingit broiled seal, which was a favorite meal [129]. Apart from boiling, the Southeast Alaskan cultures also smoked, fried and dried the meat, and ate smoked seal meat dipped in oil [132]. Traditionally, the Kyuquot roasted the meat on coals during potlatch. More modern methods of cooking used include boiling or frying [134].

The Kwakiutl and Eyak kept the blood [69, 126], adding it to broth for soup [69]. The Kwakiutl added organs and blubber to the soup [126].

The Bella Coola, Southeast Alaskan cultures (including Tlingit and Tsimshian) and Eyak used the oil [69, 129, 130, 132, 133]. The Tlingit consumed the oil, especially during feasts, and also used it as an item of trade [129]. The Southeast Alaskan cultures consumed the oil, as did the Eyak, who also used it to preserve dried clams [69, 132]. Sometimes, the Eyak obtained the oil by trade from other cultures [69]. The Quileute, Kwakiutl and Eyak used the blubber [69, 126, 137]. The Eyak gave their infants seal blubber attached to a stick to suck and the Kwakiutl consumed the blubber with dried halibut or salmon [69, 126]. The Quileute traded the blubber for oysters, sockeye salmon, and eulachon grease from the neighbouring cultures [137].

The American Paleo Arctic people in the Choris Peninsula are thought to have cooked seal in a hearth-type oven made of limestone, probably in a cooking pot [64]. The Thule are thought to have cached seal for later use [34].

The Tillamook steamed seal in ovens or boiled it in vessels into which were tossed hot stones [50]. The Coast Salish broiled, steamed, boiled, roasted or baked seal [5, 7, 8]. They often boiled it with hot stones, adding vegetables towards the end of cooking. Sometimes, they roasted it in a ditch [8], or steamed it in an earth oven [7]. The Nootka Aht consumed the flesh boiled, using a wooden vessel filled with water and hot stones [54]. The Kwakiutl consumed the flesh boiled or steamed. They boiled it in vessels filled with water and hot stones. They steamed it over hot, wet stones which had previously been placed in a vessel or a pit [70]. The Haida smoked or dried the flesh for storage [10]. Tlingit women prepared the flesh for consumption, boiling it in baskets filled with water in which they tossed hot stones [27]. The Eyak of Copper River Delta, Alaska boiled seal flesh in spruce baskets filled with hot stones [69].

Nunivak Yupik froze or dried seal for later consumption [29]. St. Lawrence Island Yupik consumed it raw, boiled, aged, or dried, storing the meat in underground rooms to age [78]. The Coastal Chukchi consumed seal flesh cooked, fermented or raw, and also consumed seal muktuk (or muntuk) [40].

Inuit consumed seal mostly raw (fresh or frozen), but sometimes boiled, dried, aged or as part of a soup [74, 83, 85, 98, 101]. A stone lamp fuelled with animal fat was sometimes used to boil or stew it. Alternatively, they boiled it in a water-containing vessel close to a fire [73]. Tununeremiut Inuit women prepared the seal for consumption, by skinning and butchering it and taking only enough meat for each meal. Tununeremiut traditionally consumed seal raw; however, by the 1960s, it is reported that they were cooking it more often by either boiling or occasionally frying [31]. Central Inuit consumed seal either boiled or frozen raw, and Quebec Inuit usually consumed it aged, but sometimes consumed it boiled, raw, dried, congealed, or smoked [14, 91].

Greenland and Labrador Inuit ate the flesh raw, but also boiled and fermented it. They often dipped the flesh in oil. Greenlanders cooked the flesh with blubber [74]. East Greenlanders consumed seal boiled, dried, or frozen and stored the dried flesh in blubber bags [41]. Labrador Inuit cached seal for later use in reserves made of stone [58].

The Micmac roasted seal meat on an open fire, either on a stick or on a rope attached to two poles, and used sharpened bones as knives [60].

Seal was an occasional food source for James Bay Cree (of Fort George, Eastmain and Paint Hills) [9, 75] and Attawapiskat Cree [48]. When Attawapiskat did eat it, they are reported to have boiled the flesh [24]. The West Main Cree generally did not eat seal, feeding it to their dogs instead [25].

Other seal parts were consumed apart from the flesh. The People of Port Simpson ate the heart and liver after it had been soaked in brine to remove the blood and the “wild taste” [96]. The Eyak considered seal flipper a delicacy. They also preserved the blood and added it to broth to make soup [69]. St. Lawrence Island Yupik consumed the skin and internal organs [78]. Inuit consumed seal liver, usually raw and immediately after the seal was butchered. Seal blood was also a common food [101]. Tununeremiut are reported to have eaten the heart and liver [31]. Inuit of Arctic Bay boiled the liver occasionally [83] and Central Inuit consumed every part of the seal and added seal blood to broth to make a soup [73, 91]. Copper Inuit consumed sealskin with raw blubber [74]. The Chugach and Inuit of Greenland and Labrador also consumed seal blood in a blood soup. Inuit of Greenland and Labrador also consumed the liver, kidney and heart, usually consuming the liver raw, which was a childhood favourite. They often prepared seal broth and consumed it as a hot beverage. The Micmac consumed the flesh and internal organs, with the exception of gall bladder, and boiled or roasted the intestines [60].

Cultures reported to have used the blubber (fat) and/or the oil extracted from the blubber (by boiling the blubber) include Chinookans of Lower Columbia, Coast Salish, Squamish, Nootka, Kwakiutl, Haida, Eyak, Yupik (including those from Kasigluk, Nunapitchuk, St. Lawrence Island and Nunivak), Inupiat (including those from Point Hope, Wainwright), early Birnirk culture, Chukchi, Inuvialuit, Inuit (including Copper, Central, Tununeremiut and those from Netsilik, Iglulik, Baffinland, Labrador, Greenland), Attawapiskat Cree, West Main Cree, Micmac of Richibucto and Passamaquoddy [2, 7, 8, 24-26, 29, 31, 38, 40, 41, 43, 51, 53, 56, 57, 64, 66, 68-70, 73, 74, 78, 79, 81, 84, 91, 94, 97-101, 103, 107, 108, 119].

The Coast Salish extracted the oil by boiling the blubber in a vessel containing water in which hot stones were tossed and served the oil (placed in clam shells at times) with dried food including dried meat [7, 8, 57]. They also consumed the oil during feasts and stored the oil in a seal bladder [8, 57]. The Squamish consumed the blubber and oil [107]. The Kwakiutl consumed the blubber, preparing it by boiling it in water-filled vessels in which they tossed hot stones. They placed the cooked blubber in rectangular plates and ate it with their hands [26].

Alaskan cultures used the oil, mixing it with the contents of caribou stomach [99]. The Eyak consumed the oil, used it to preserve dried clams, and sometimes obtained it by trading with other cultures. Eyak often gave blubber attached to a stick to infants to suck [69]. Chukchi consumed seal oil with caribou meat [40].

Inuit sometimes ate the meat and blubber mixed together, and it was the women’s job to mix the meat and blubber together by mastication [79]. The women also chewed the blubber to extract the oil which was used to make a special kind of chewing gum [68, 81]. Central Inuit consumed the blubber only when other types of food were scarce [70, 91, 103]. Tununeremiut used the oil to make bannock [31]. The Attawapiskat consumed seal blubber and diced and fried it for storage [24]. West Main Cree extracted the oil from blubber and used the oil as a dipping sauce with dried fish [25]. The Micmac of Richibucto consumed the oil, served it at feasts, used it to cook and as fuel [53]. The Mi’kmaq extracted the oil by boiling the blubber, consumed it at feasts and used it to cook fish and as fuel for lighting purposes. They applied the oil directly on their skin as protection against cold and rain and traded the oil with neighbouring tribes [43].

Uses other than food

Seal oil/blubber was often used as fuel. This was reported for Inuit (including those of Cape Krusenstern, Labrador, Baffinland, Iglulik, Greenland) and Inuvialuit [64, 66, 68, 74, 78, 79, 81, 84, 94, 97, 98, 100, 101, 119]. The oil served as an important item of trade for some cultures including Nunivak Yupik, Labrador Inuit and Greenland Inuit [29, 74].

Seal byproducts were also used for therapeutic purposes. Greenland and Labrador Inuit sometimes used the oil as a laxative, and seal blood soup was given to nursing Eyak to facilitate lactation [69, 74]. Pregnant Haida women swallowed seal fetus heads believing it would make labor and delivery easier [140]. Seal blood soup was given to nursing Eyak mothers, as it was believed that it facilitated lactation [69].

Seal bladder, stomach and skin were often used to store oil [2, 3, 7, 29, 56, 57, 60, 66]. The Micmac, Bella Coola and Coast Salish used the stomach to store oils of various kinds (in the case of the Bella Coola, the oil was eulachon) [3, 7, 60]. The Coast Salish and the Micmac used the bladders; Nunivak Yupik used the sealskin [2, 29, 56, 57, 60, 66]. The Tlingit used seal bladders to store grease or oil, and the Puget Sound culture used the skin to make hunting gear including floats and bags [128, 135, 136]. When the Kwakiutl caught an abundance of seal, they traded the heads for blankets [126].

Yupik used the skins to cover the kayaks used for hunting and the Mi’kmaq traded the skins with neighbouring tribes [43, 62].

Beliefs and taboos

Seals were important culturally. The seal hunt was associated with prestige in the Kyuquot culture and when one was caught, it was an occasion for a potlatch [134]. The Kwakiutl distributed the seal as follows: the chest was given to the head chief, the hind flippers were given to the young chiefs, and fore flippers were given to the next on the social ladder [124]. The blubber was given to the common people and the tail was given to the people of the lowest rank. The head was given to the steersman and the internal organs were reserved for the chiefs [126]. The Kyuquot reserved the right arm for the chief and the Northern Nootka and Kwakiutl chiefs had special rights on the flesh and fat [127, 134]. The Kwakiutl served seal during feasts, especially the blubber, and they used blubber eating skills as a comparison point between two chiefs during feasts [126]. The Tlingit consumed seal oil, particularly during feasts [129]. Among the Tanaina the seal hunt and the butchering of seal were reserved for men [141].

Various taboos and rituals were observed when handling or hunting seals. Menstruating Eyak women were not allowed to eat seal meat and seal flippers were never given to children [69]. The Kwakiutl took special care when preparing seal flippers to ensure success when hunting seals. Special storage and preparation were also required for the hunting material [126]. The Eyak preferred not to cook sea and land mammals together, although it was not taboo to do so [69].

Cultures of the Northern Coast of British Columbia performed rituals such as bathing or fasting before the seal hunt in order to bring good luck [89]. Tsimshian men performed a purifying ritual which included fasting, bathing, continence, and drinking the fluid of the roots of devil’s club before going seal hunting [118]. Haida men performed ritual purification one month before going seal hunting and it consisted of fasting, practicing strict continence, the usage of medicines and emetics, bathing and “abstention from water” [38].

Coast Salish asked the spirits for guidance, practiced religious ceremonies, and bathed prior to hunting [2, 5]. The killer whale was often asked for guidance by sea mammal hunters. Before the hunt, hunters had to bathe, refrain from sexual activities or from eating, and they are reported to have consumed emetics such as onions. While their husbands were out seal hunting, the wives had to remain silent and refrain from any housework or combing their hair. While on the hunt, the hunters also did not comb their hair. Once the seal was harpooned, a particular song had to be sung by the hunter [7].

Menstruating Eyak women were not allowed to eat seal meat and seal flippers were never given to children. The Eyak did not cook seal and land mammals together, although it was not thought to be a taboo to do otherwise [69]. Inuit dropped water or melted snow on the seal’s head before it was butchered. Inuit women were forbidden to eat the first seal catch of the season. The taboo was so strong, they were also not allowed to chew blubber to extract the oil, which was a typical women’s chore [81]. When an Inuit boy slaughtered his first seal, he was not allowed to eat it [73].

Inuit hunters of Baffinland and Hudson Bay avoided contact with dead corpses or menstruating women or women with recent miscarriages; otherwise Sedna, the legendary deity thought to be the mother of all seals, would be displeased. Hunters offered a small bit of moss, a small piece of caribou skin, and a sinew to the diety Nuliayoq when they went hunting seals for the first time. When a seal was taken, the hunter had to place the harpoon close the lamp in order to please its spirit and Nuliayoq. They also believed that the seal spirit remained in its body for three days after it died, after what it was sent back to Sedna. It was therefore forbidden to eat seals before those three days, otherwise, Sedna would send illnesses, hunger, or bad weather. On the other hand, they believed that if the spirit was allowed to return to Sedna, the hunters would have success in seal hunting. The women refrained from eating seal tongue and women who had just given birth could only eat seal caught by their husband, a young boy, or an older man, otherwise the “vapour arising from her body would become attached to the souls of other seals, which would take the transgression down to Sedna, thus making her hands sore”. Seal was usually shared among all the male villagers, but it had to remain in the hut of the hunter who invited the men to his house to eat the seal in order to avoid inadvertent contact with individuals who were under taboo, and who would incur the wrath of the seal and Sedna towards the hunter. This was especially the case for the first catch of the season. It was forbidden to give seal bones to dogs, so the bones were thrown into the sea. Women offered white-tanned seal pelts to Kadlu, another deity, when thunder was heard as they believed that thunder was a sign that Kadlu needed the pelts. Everyone, male and female had to avoid any contact between walrus and seal, thus they changed or took off their clothes before eating seal during the walrus season [12].

Iglulik and Central Inuit of Northern Hudson Bay are reported to have consumed Steller sea lions [91], but this seems unlikely given North American sea lions are restricted to the Pacific Ocean.

Hunting

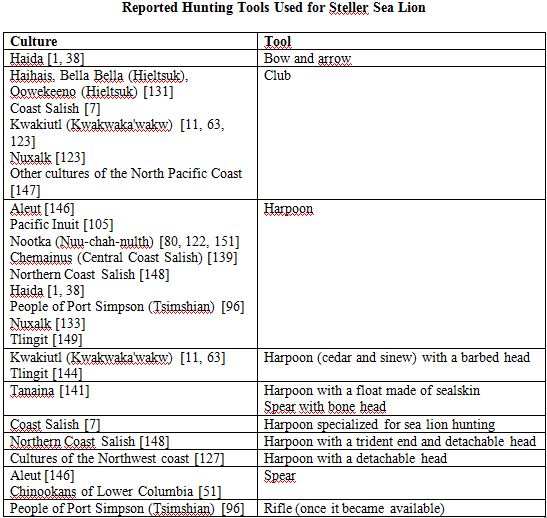

Steller sea lion is reported to have been hunted spring through fall [57, 96, 106, 107, 118, 138]. Clubs, harpoons and spears were most commonly used (see table).

For the Coast Salish [2, 5], Tlingit [144] and Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth) [80], the Steller sea lion hunt brought prestige to successful hunters.

While some cultures of the northwest coast, including the Chemainus and the people of Port Simpson, hunted Steller sea lions in canoes on open waters [86, 96, 139], others, including the Coast Salish [7], Haihais [131], Bella Bella (Hieltsuk) [131], Oowekeeno (Hieltsuk) [131] and Chinookans of Lower Columbia [51], preferred to hunt on the shore. The Haida are reported to have used both methods. They hid behind screens when hunting on the shore [38]. Sitka Tlingit are reported to have taken sea lion stranded on the shore [129].

Preparation

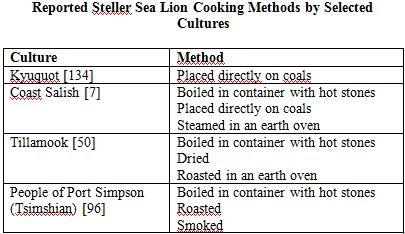

While Inuit ate sea lion meat raw [143], other cultures cooked it.

The people of Port Simpson soaked all parts to be eaten before cooking, to remove the “wild taste” [96]. A variety of sea lion parts were eaten. The Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw) [11], Tlingit [136], and Coast Salish [5, 7] consumed sea lion meat. The Tlingit [129] and Haida [38] used sea lion oil. The Chinookans of Lower Columbia [51] consumed its meat, blubber, and oil. The people of Port Simpson [96] used sea lion heart, liver and meat. The Southern Kwakiutl and Nuxalk found sea lion meat bitter [123].

The Tlingit [129] and the Coast Salish [57] served sea lion during feasts. The right arm of the sea lion was reserved for the Kyuquot chief [134]. The Coast Salish [5] shared sea lion between all members of the community, while the Chemainus [139] shared it amongst the hunters who contributed to the killing, depending on the order in which they harpooned it.

Uses other than food

Some Indigenous People used sea lion parts for collection or storage or collection. For example, the Kwakiutl [11] and Coast Salish [5] used intestines to make strings for bows; Coast Salish [5] used the stomach to store liquids; some cultures of the Northwest coast [127] used the bladder as a float on harpoons.

Inupiat (including those of Nuiqsut, Point Barrow and Kotzebue Sound), Yupik (including those of St. Lawrence Island), Inuvialuit, Inuit (including Copper, Netsilik, Iglulik and those of Grise Fiord, Starnes Fiord, Baffin Island, Clyde, Cumberland Sound, Qikiqtarjuaq - formerly Broughton Island, Southampton Island, Belcher Island, Ungava Bay, Labrador, Nordost Bay, Greenland), Dene, Omushkego Cree, Naskapi (Innu), Thule, Inugsuk culture and possibly Beothuk are reported to have consumed or hunted ringed seal [14, 15, 30, 34, 61, 68, 74, 84, 91, 109, 110, 115, 125, 142, 143, 152-178].

Ringed seal was an important food source for Western and Eastern Arctic coast cultures and other circumpolar cultures in winter [30, 61, 74, 115, 143, 152-154, 157-159, 161, 164-167, 170-173]. Ringed seal was the most important seal species for Clyde Inuit and its pursuit drove the winter activities. In summer, they sometimes participated in feasts called nirriyqktuqtuq, where ringed seal was shared [172]. Northern Hudson Bay Inuit particularly valued the meat [91]. Ringed seal was one of the most preferred meat and oil sources of many Inuit [143, 172].

Hunting

Ringed seal have been and continue to be available at different times in different regions.

Northwest Alaskans are reported to have hunted in winter and June/July. Point Barrow Inupiat are reported to have hunted October to July, Nuiqsut in July, September and December; St. Lawrence Yupik hunted in summer, early fall and winter [84]; Mackenzie Delta Inuvialuit are thought to have hunted in spring [109, 158, 166, 167]. Copper and Netsilik Inuit hunted between December and April, Northern Hudson Bay Inuit mainly in winter, and Clyde Inuit year round, but primarily in winter [91, 142, 172, 179]. Cumberland Sound, Ungava Bay, Central and Labrador Inuit reportedly hunted year-round [14, 71, 115, 121, 143, 156, 166, 169, 170]. West Greenlanders hunted in winter, spring and summer [161]. Naskapi hunted ringed seal in March/April, and September/October [177]. Hopedale Inuit are reported to have hunted year-round either on the floe edge (December to May) or on open water [125]. Inuit and Dene consumed ringed seal as a major food source, and ringed seal was especially important to Hopedale Inuit between break-up and freeze-up [125, 178]. In the Beothuk region, ringed seal was reported to have been available March to June and for Nordost Bay, Greenland, April to June [68, 176].

Ringed seal was hunted on open waters (usually from kayaks), from ice or floe edges, and on ice according to the region and season [14, 34, 68, 84, 91, 109, 115, 142, 143, 152, 158, 161, 166-170, 172, 179]. Harpoon/spear, club, bow and arrow, net, and in later times, rifle were used to hunt ringed seal [14, 91, 115, 142, 143, 152, 161, 166-168, 172, 179]. Ringed seal was commonly hunted at their breathing holes in winter; dogs were sometimes used to find these holes [168].

In fall and winter, Inupiat of Northwest Alaska hunted at breathing holes, using harpoon and rifle, and nets at night. When installing their nets, they took advantage of cracks that appeared in the ice and they made gentle sounds by scratching the ice with a special tool made of seal claws in order to lure them. They brought the catch back to camp on dog sleds. From April to June/July, they hunted on open waters in umiaks with harpoon and rifle to slaughter them. In June/July, they also hunted those basking on the ice, but these were more difficult to catch because they were easily frightened [109, 166, 167]. Central Inuit hunted in winter at breathing holes with a weapon called an unang: a light harpoon with a detachable head, a knob made of ivory, a shaft of wood, bone or ivory, according to availability. They also hunted ringed seal with an agdliaq [71]. Labrador Inuit hunted at breathing holes during winter and in open waters during summer [121].

St. Lawrence Island Yupik hunted at floe edges or at breathing holes during winter, and hunted on open water in summer and fall in umiaks propelled with paddles. During summer and fall, they also hunted from the shore [84].

Copper and Netsilik Inuit hunted in groups of about one hundred people between December and April at breathing holes. They used dogs to find the breathing holes and bring the catch home. They used spears to slaughter the ringed seals [142, 152, 179]. Copper Inuit reportedly did not hunt on open water. They used harpoons made of bone, wood, antler and copper or iron [142].

Baffinland Inuit used “traditional weapons” to hunt ringed seal, but later switched to rifles. Baffinland Inuit hunted at seal breathing holes or on ice edges during winter, and on ice edges and on the surface of the ice during spring. The breathing hole method was the most widely employed method for the winter hunt, while the surface method on ice was most efficient for the spring hunt [115]. Clyde Inuit hunted in winter (from mid-October until May) at breathing holes using a technique called maulkpuq. From spring to summer, they used a hunting technique called uuttuq, where they stalked seal basking in the sun. When the water was open, generally from mid-July, they hunted from boats using rifles [143, 172]. Cumberland Sound Inuit are reported to have hunted year-round: at breathing holes in winter, on ice when they were basking on the ice in April, and on open waters when the ringed seals had moved further from shore in summer [169].

Quebec Inuit are reported to have hunted ringed seal on open water from kayaks using harpoon and lance. Northern Hudson Bay Inuit hunted in winter at breathing holes with harpoons [14, 91]. Labrador Inuit hunted at their breathing holes during summer and on the ice during spring [170].

West Greenlanders hunted on the ice and at floe edges during winter and spring, and on open waters in summer. In winter, they also hunted at breathing holes and in the spring, they sought those basking in the sun [68, 91, 161]. When kayaking, West Greenlanders used specialized harpoons with a detachable, barbed head or unbarbed lances with a fixed head and throwing boards to throw the harpoons. Sometimes, they used nets, and in later times, rifles were used. As reported for other seal species hunting by this culture, on ice in winter, they also practiced a type of cooperative hunting technique called “peep” hunting, where one of the hunters would attract the ringed seal, and the other would kill it.

Preparation

The flesh was consumed boiled, smoked, fermented, dried and raw (fresh or frozen) [14, 74, 91, 143, 161-163, 171, 173]. Inuit typically consumed ringed seal raw and often stored frozen ringed seal for later winter use [143]. Quebec Inuit reportedly consumed the flesh aged, boiled, raw, dried, congealed, or smoked; Belcher Island Inuit consumed it raw-fresh or raw-frozen, cooked or dried [14, 171]. Baffin Island and Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit also consumed ringed seal pup meat [173]. Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit consumed it boiled, raw or aged and Inuit of Northern Hudson Bay consumed it boiled or frozen raw [91, 162, 163]. West Greenlanders usually boiled the fresh flesh or consumed the flesh aged, and often froze the raw flesh for later use, at which point it was consumed raw frozen. Sometimes, they dried the raw flesh for later use [161]. When cooking seal, Greenland Inuit cooked it with blubber [74].

Other ringed seal parts were also consumed. Northern Hudson Bay Inuit consumed every part of the ringed seal and they added its blood to ringed seal broth to make a soup [91]. Greenland and Labrador Inuit consumed ringed seal blood in soup. Greenland and Labrador Inuit also consumed the liver, kidney and heart, usually consuming the liver raw. They often prepared ringed seal broth and consumed it as a hot beverage. Baffin Island Inuit consumed the brain, eyes and intestines. Iglulik Inuit consumed the brain and Point Barrow Inupiat are reported to have consumed the eyes. Iglulik Inuit and Copper Inuit also consumed ringed sealskin with blubber. Iglulik Inuit also cooked ringed seal pup stomachs when they were full of milk and the final product tasted like cheese [74]. West Greenlanders distributed small strips of ringed seal skin and blubber to the children [161]. Inuit of Quebec consumed dried ringed seal ribs, loins, entrails and braided small intestines [14]. Inuit of Starnes Fiord consumed the liver and Belcher Island Inuit consumed the intestine cooked or dried, the heart raw or cooked and the liver, brain, eyes, kidney, tongue and mustache liver [155, 159, 162, 163, 171]. Baffin Island Inuit consumed the broth and liver, Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit consumed boiled ringed seal broth, aged flippers and the raw liver, heart, brain and eyes [173].

Yupik, (including those of St. Lawrence Island), Inupiat, Inuit (including those of Starnes Fiord Northern Hudson Bay, Baffin Island, Qikiqtarjuaq, Cumberland Sound, Belcher Island, Labrador and Greenland) are reported to have used the blubber and/or the oil extracted from the blubber [74, 84, 91, 143, 155, 159-163, 167-171, 173]. Ringed seal oil is reported to have been the preferred source of oil for Inuit [143].

Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit consumed the blubber aged, raw or boiled. They also consumed ringed seal pup blubber raw or boiled [162, 163]. West Greenlanders distributed small strips of skin and blubber to their children and Belcher Island Inuit consumed the blubber “fresh” or aged [161, 171]. Copper Inuit and Iglulik Inuit consumed ringed seal skin with the blubber, usually raw, and Greenland Inuit used the blubber in cooking. Greenland and Labrador Inuit used the seal oil and blubber as a dipping sauce for dried fish and meat [74].

Uses other than food

Greenland and Labrador Inuit used the blubber as a source of fuel and an item of trade; the west Arctic coast cultures also used it for trading. Inupiat of Northwest Alaska, St. Lawrence Island Yupik and probably Inuit of Labrador used it as a source of fuel [74, 84, 143, 167, 168, 170]. Labrador Inuit used ringed seal skins to make kayaks [121].

Greenland and Labrador Inuit sometimes used ringed seal oil as a laxative [74]. Inuit (including Caribou and those of Southampton Island, Grise Fiord and Starnes Fiord) also used ringed seal as dog food [74, 155, 157].

Ringed seal was an important cultural resource with some taboos and rituals. Copper Inuit could not store ringed seal meat with caribou meat and ringed seal blood could not be used to splice arrows used in the caribou hunt [142]. St. Lawrence Island Yupik believed the ringed seal had a soul similar to theirs, so they prayed for its soul before killing it [84].

Ringed seal was reported to be a significant source of PCB contamination in the traditional diet of Inuit of Qikiqtarjuaq [164].

Cultures reported to have hunted bearded seal include Dene, Inuvialuit, Inuit (including Copper and Caribou Inuit; Inuit of Cape Parry, Coronation Gulf, Victoria Island, Netsilik, Grise Fiord, Iglulik, Baffin Island (Clyde), Qikiqtarjuaq - formerly Broughton Island, Cumberland Sound, Southampton Island, Belcher Island, Labrador, Greenland; and Thule), Naskapi, Beothuk, Yupik (including those of Nunivak and St. Lawrence Island), Inupiat (including those of Barrow, Kotzebue Sound and Nuiqsut), Norton, Chukchi and Koryak [14, 15, 17, 29, 40, 58, 64, 68, 74, 84, 91, 104, 109, 110, 142, 143, 152, 157-163, 165-176, 178, 180-182]. Labrador Inuit are also reported to have consumed bearded seal [121], as did Nuiqsut Inupiat, Copper Inuit, Ungava Bay Inuit, Labrador Inuit of Hopedale and Naskapi (Innu) of Davis Inlet [109, 125, 142, 156, 177].

Bearded seal was hunted at different seasons or year-round according to region and culture. It was an important food source for many Inuit in winter [143]. Cultures reported to have hunted in winter include Inupiat [167, 169], St. Lawrence Island Yupik [84, 161] and Inuit (including Copper, Netsilik, Labrador, Cumberland Sound and West Greenland [58, 91, 142, 152]. Other cultures also hunted spring through fall. Inuvialuit of Mackenzie Delta probably hunted bearded seal during spring, Point Barrow Inupiat and St. Lawrence Island Yupik sometimes hunted in spring, but mainly during summer and fall, and Thule (neo-Inuit) hunted during summer [84, 110, 158, 166]. Inuit on the northern part of west Greenland hunted during spring and summer [161]. Clyde Inuit sought bearded seal when the waters were open, from July to October [143, 172]. Caribou Inuit of Eskimo Point hunted from mid-April, and sometimes during fall if there was a caribou shortage [182]. In the Beothuk region, bearded seal was available April to May [176]. Nuiqsut are reported to have hunted in September [109]; Copper Inuit in winter [142]. Ungava Bay Inuit hunted in winter [156] and Labrador Inuit November to May [125]. Naskapi hunted in September/October and March/April [177].

Bearded seal was hunted on open waters (usually from kayaks), on sandy or rocky shores, from ice or floe edges and on ice according to region and season [17, 58, 84, 91, 109, 142, 143, 152, 158, 161, 166, 167, 169, 170, 172, 182]. Harpoons/spears, clubs, bows and arrows, nets, and in latter times, rifles were used [14, 91, 104, 142, 143, 161, 166, 172, 182].

Inupiat of Northwest Alaska hunted mostly on open water using nets anchored with rocks and made buoyant by sealskin or bladder floats [104]; they also sought bearded seal at breathing holes in winter [109, 167]. Barrow Inupiat are reported to have hunted from umiaks with harpoons or rifles [166]. St. Lawrence Island Yupik hunted at floe edge or at breathing holes during winter, and on open water in umiaks propelled with paddles or from the shore during summer and fall [84].

Mackenzie Delta Inuvialuit probably hunted on ice during spring [158]. Inuit are reported to have hunted bearded seal with harpoons during winter at breathing holes, and took advantage of the winter darkness by installing nets that were not seen by the seal [143]. Copper Inuit hunted bearded seal alone, locating breathing holes in the ice during winter months and using harpoons made of bone, wood, antler and copper or iron; dogs were used to carry the catch home. They are reported to not have hunted bearded seals on open water [142]. Netsilik Inuit hunted mainly in winter at breathing holes, taking advantage of the snow cover to dampen the sound of their steps [152]. Caribou Inuit of Eskimo Point hunted from mid-April, on floe edges. They are reported to have used rifles in later times [182]. Iglulik Inuit of Melville Peninsula and northern Baffin Island hunted bearded seal at the floe edge or at their breathing holes [17]. Clyde Inuit hunted on open waters from boats, circling the seal with boats and shooting with a rifle [172]. Inuit of Cumberland Sound hunted at floe edges during winter and on open waters when possible [169]. Northern Hudson Bay Inuit harpooned seal at their breathing holes [91], and Quebec Inuit used harpoons and lances. At times, they hunted alone although this was considered dangerous [14]. Labrador Inuit took seal on the ice or shore, according to the season [170], or from floe edges [125, 142]. During winter until mid-January, they searched for seal breathing holes [58, 91, 142, 152]. Copper Inuit did not hunt bearded seal on open water. They hunted at the seal’s breathing holes using harpoons made of bone, wood, antler, and copper or iron. Dogs helped to bring the catch home. Labrador Inuit hunted bearded seal

West Greenland Inuit hunted on the ice and at floe edges during winter/spring and on open waters during summer. When kayaking, they used a specialized harpoon with a detachable, barbed head and a throwing board or a lance with an unbarbed, fixed head. They also used nets and rifles in latter times. In spring, seal could be harpooned while basking in the sun. On ice in winter, they hunted cooperatively using “peep” hunting: one hunter would attract the seal and another one would kill it with a harpoon. When approaching seals at breathing holes, hunters put skins on their feet to silence their steps [161].

Preparation

The flesh was consumed boiled, fermented, dried, aged, smoked, raw-fresh and raw-frozen [14, 74, 162, 163, 171].

Inuit are reported to have often cached bearded seal in frozen piles for later use. Inuit, including Caribou Inuit, are reported to have eaten the flesh raw (either frozen or fresh) [74], but a stone lamp fuelled with animal fat was sometimes used to boil or stew it. Copper Inuit, especially those of Coronation Gulf, are reported to have cooked seal more often than did other Inuit [143]. Northern Hudson Bay consumed bearded seal boiled or frozen raw; Quebec Inuit consumed it aged, boiled, raw, dried, congealed or smoked [14, 91]. Belcher Island Inuit consumed it cooked (method not specified), raw or dried and Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit consumed it boiled, raw or dried [162, 163, 171].

West Greenlanders consumed bearded seal boiled, aged or fermented, and raw-frozen. They often dipped the flesh in oil before eating it [74] and sometimes dried the raw flesh for later consumption [161].

Many consumed other parts of bearded seal. Inuit of Northern Hudson Bay consumed every part of the seal; they added seal blood to seal broth to make soup [91]. Chugach, Greenland Inuit and Labrador Inuit also consumed bearded seal blood in a soup. Greenland Inuit and Labrador Inuit consumed the liver, kidney and heart; they usually consumed the liver raw, which was a childhood favourite. They often prepared bearded seal broth and consumed it as a hot beverage [74]. West Greenlanders distributed small strips of bearded seal skin and blubber to children [161]. Quebec Inuit consumed dried bearded seal small intestines [14]. Belcher Island Inuit consumed the intestine cooked or dried, the flippers aged, raw, or cooked as well as the tongue and heart [171]. Qikiqtarjuaq Inuit consumed raw or boiled intestines, and the raw liver [162, 163].

Yupik St. Lawrence and Inuit (including those from Hudson Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Cumberland Sound, Labrador and Greenland) are among the cultures known to have used the blubber (fat) and/or the oil extracted from the blubber [74, 84, 91, 143, 159, 160, 162, 169, 170]. Northern Hudson Bay Inuit consumed the blubber, but only when other types of food were scarce [91]. Inuit of Qikiqtarjuaq consumed the blubber boiled or raw [162]. Greenland Inuit consumed bearded sealskin with blubber, usually in the raw state. They also used the blubber to cook. Greenland and Labrador Inuit used bearded seal oil and bearded seal blubber as a dipping sauce for dried fish and meat.

Sharing was a central theme for many, and this included sharing harvested bearded seal, which is reported for Inuit of Northern Hudson Bay, Quebec, Labrador and West Greenland [14, 91, 143, 161, 165]. Among Inuit of Quebec, the heart and flesh of the dorsal vertebrae were consumed by the women of the community and the lumbar vertebrae were consumed by the men [14].

Uses other than food

Inuit reported to have often fed bearded seal to dogs include those of Southampton Island, Eskimo Point (Caribou Inuit), Clyde and Grise Fiord [74, 157, 171, 172, 182].

Some found bearded seal more important as a material resource. With bearded seal skin, Inupiat made umiaks (whaling boats), covers for umiaks and walrus lines [166, 181]. Clyde Inuit hunted it mostly for the skin [172]. Inuit (including those of Cape Parry, Coronation Gulf and Victoria Island) used the skin to make umiaks, clothing, harpoon lines, dog harnesses and boot soles [143, 168]. Greenland and Labrador Inuit sometimes used the oil as a laxative [74].

Greenland and Labrador Inuit and St. Lawrence Island Yupik used the blubber as a source of fuel and as an item of trade [74, 84, 143, 170].

Beliefs and taboos

Copper Inuit avoided storing bearded seal meat with caribou meat; bearded seal blood was not used to splice arrows used in the caribou hunt [142]. St. Lawrence Yupik believed the bearded seal had a soul similar to theirs, so they prayed for its soul before the slaughter [84].

Coastal Washington and British Columbia cultures (including Salish, Tlingit and Nootka [Nuu-chah-nulth] of Vancouver Island), Inuit (including Caribou, Central, Ungava Bay, Labrador and Greenland Inuit), Chugach Yupik, Eyak, Aleut, Wampanoag, Micmac (Mi'kmaq) of Richibucto and Eastern Abenaki are reported to have hunted harbor seal [16, 37, 46, 53, 68, 69, 74, 105, 124, 143, 144, 147, 148, 150, 151, 156, 161, 165, 170, 174, 176, 182-184]. The Tlingit and Tanaina of Cook Inlet are also reported to have hunted and eaten harbour seal [149, 185]. Southeast Alaska cultures are reported to have preferred harbour seals over northern fur seal [132].

Hunting

Availability of harbor seal varied according to region. It was available in the Beothuk region early March to late November (being most abundant from mid-May to mid-June) [176]. West Coast cultures are reported to have hunted harbor seal in spring and summer [46]. The Nootka hunted late spring [151] and the Eyak hunted them mainly in summer [69]. The people living on the northern part of west Greenland hunted during winter, spring and summer [161], and Chugach hunted them winter to spring [105]. Harbor seal was an important source of subsistence for Inuit mainly in winter, but was also available at other times of the year [143]. Caribou Inuit of Eskimo Point hunted from mid-April [182]. It was available to Labrador Inuit year-round [68, 143, 170]. Few harbor seals were available to Ungava Bay Inuit in summer [156]. Eastern Abenaki hunted them during the “warm” months [184].

Harbor seal was hunted in open waters (usually from kayaks), on the shore, from ice or floe edges and on ice according to the region and season. Pacific cultures hunted harbour seal from the shore or from kayaks/canoes from April through October; they were also taken when the seal was resting on the shore [105, 147]. The Northern Coast Salish are reported to have hunted harbour seal on shore and in canoes on open water [148]. The Eyak hunted them where it was available according to season: open waters, sandy or rocky shores, or on ice. In summer, they hunted them on the river shore [69]. Inuit hunted them during winter at the breathing holes [143]. Caribou Inuit of Eskimo Point hunted harbour seal from mid-April on floe edges [182]. West Greenland Inuit hunted on the ice and at floe edges during winter and spring and on open waters during summer. In winter, they also hunted at their breathing holes [161]. The Chugach hunted harbor seal while they were resting on rocks [68].

Harpoons/spears, clubs, bows and arrows, nets, and in later times, rifles were used to hunt harbor seal [37, 69, 105, 143, 144, 147, 148, 151, 161]. British Columbia Coast and Locarno Beach (Obisidian culture type) cultures used toggling harpoons. Tlingit used canoes and toggling harpoons [37, 144]. When hunting on shore, the Tlingit disguised themselves in sealskin and used a harpoon or a club [149]. The Tanaina hunted in summer with bow and arrow or toggle harpoon and hunted in winter at their breathing holes [185]. The Northern Coast Salish used specialized hunters who hunted in teams of two, using a canoe and a harpoon with a detachable head. They also hunted harbor seals on the shore: the hunter mimicked the harbor seal’s behaviour and cry in order to get close enough to club or harpoon it [148]. The Nootka who hunted them in late spring, used clubs, harpoons, stakes disguised in seaweed, or nets [147, 151].

In summer, the Eyak used clubs (or sometimes harpoons) to hunt seal on the river shore. They also mimicked the harbor seal’s behaviour and cry to lure it [69]. The Chugach hunted those resting on the rocks, using a stuffed harbor sealskin as a decoy [68].

Inuit hunted harbor seal at their breathing holes in winter with harpoons and nets [143]. They also used kayaks on open water. When hunting on-shore, they used decoys to attract them. They also used clubs or nets to hunt harbor seals [105].

When kayaking, West Greenlanders used a specialized harpoon with a detachable, barbed head or an unbarbed lance with a fixed head. They also used bladder darts (except in the northern region after early 1900s), nets, and, in later times, rifles. In January, they hunted harbor seal at their breathing holes using specialized harpoons or “kayak” harpoons. Hunters put skins on their feet to silence their steps. On ice in winter, they also practiced a type of cooperative hunting technique called “peep” hunting, where one of the hunters would attract the harbor seal, and the other would kill it. In the southern part, bladder darts were used during this collective hunt. In spring, they also harpooned those that were basking in the sun [161].

Harbor seal is known to have been an important subsistence resource for some ancient cultures, including Southeastern Alaska cultures during the late phase (1000 A.D. to 1700 A.D.) [16]. Central Inuit, Aleut and several cultures of Alaska relied on harbor seal for subsistence [74].

Others relied less on harbor seal. Labrador Inuit and Greenland Inuit are reported to have consumed harbor seal occasionally [161, 165]. Caribou Inuit ate it occasionally, but more typically used it as dog food [182]. The Wampanoag consumed harbor seal, but they no longer consumed it by the late 1940s [183].

Preparation

Harbor seal flesh was consumed boiled, fermented, dried and/or raw (either fresh or frozen) [69, 74, 143, 161]. The Eyak boiled the flesh in baskets made of spruce, using the hot stones method [69]. Inuit ate it raw most of the time [74, 143]. Labrador Inuit boiled the flesh, and also ate it fermented as well as fresh. Since harbor seal meat is dry, Labrador usually dipped it in oil before eating it. Greenlanders boiled the fresh flesh, but often froze the raw flesh for later use, at which point it was consumed raw frozen. Sometimes, they dried or fermented the flesh for later use [161]. They often ate seal meat dipped in oil, and also consumed the skin with blubber, usually raw [74].

Other harbor seal parts were also consumed. The Eyak consumed harbor seal flippers, considered a delicacy. They also preserved the blood and added it to broth, to make soup [69]. The Chugach, Greenland and Labrador Inuit also consumed harbor seal blood in soup. Greenland and Labrador Inuit consumed the liver, kidney and heart. They usually consumed the liver raw, which was a childhood favourite. They often prepared harbor seal broth and consumed it as a hot beverage [74]. West Greenlanders distributed small strips of harbor seal skin and blubber to children [161].

Eyak, Inuit (including those of Labrador, and Greenland), and Micmac of Richibucto are reported to have used the blubber (fat) and/or the oil extracted from the blubber [53, 69, 74, 143, 161, 170]. In addition to the flesh, Tlingit consumed harbour seal blubber, and extracted oil from the blubber [149]. The oil and skin were used as trade items [149].

Uses other than food

Harbor seal was also used for therapeutic purposes. Harbor seal soup made with the blood, was given to nursing Eyak mothers, as it was believed that it facilitated lactation [69]. Greenland and Labrador Inuit sometimes used the oil as a laxative [74].

Beliefs and taboos

Harbor seal was important culturally, and various taboos and rituals were observed when handling or hunting it. For Kwakwaka’wakw, the harbor seal chest and other choice parts were reserved for the chief [124]. The Tlingit used the humerus bone of harbour seals to foretell the future [149]. Menstruating Eyak women were not allowed to eat harbor seal meat and harbor seal flippers were never given to children. The Eyak preferred not to cook sea and land mammals together, though it was not taboo to do otherwise [69].

Inuvialuit, Inupiat (including Kotzebue Sound, Nuiqsut and Point Barrow), St. Lawrence Island Yupik, and Aleut are reported to have hunted spotted seal [74, 84, 104, 109, 158, 166, 167].

The Inuvialuit hunted in late spring on the ice [158] and Inupiat of Northwest Alaska hunted mainly in summer [109, 167]. Inupiat used nets anchored with rocks and maintained buoyant with sealskin or bladder floats [104, 167]. Nuiqsut Inupiat may have hunted them in December on ice [109]. St. Lawrence Island Yupik hunted in summer, early fall and winter. During winter, they hunted at floe edges or at breathing holes, and during summer / early fall on open water in umiaks propelled with paddles and from the shore [84].

Aleut and several cultures of the Bering Strait relied on spotted seal for subsistence [74]. Others relied less on harbor seal. Inupiat and Inuvialuit are reported to have consumed spotted seal occasionally [158, 167]. Nuiqsut ate spotted seal, but it was not a preferred food choice; it was hunted mainly for the skin [109].

St. Lawrence Island Yupik are reported to have used the blubber (fat) and/or the oil extracted from the blubber [84].

Point Barrow Inupiat used harbor seal skin to make floats used for whaling [166].

St. Lawrence Yupik believed harbor seal had a soul similar to them, so they prayed for the harbor seal’s soul before killing it [84].

Pacific coast cultures including Makah, Quileute, Salish, Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth), Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw), Nuxalk, Haihais, Bella Bella (Hieltsuk), Oowekeeno (Hieltsuk), Tlingit; Inuit; Alaskan Coast cultures including Aleut and Tanaina; and Chugach are reported to have consumed and/or hunted northern fur seal [1, 46, 68, 91, 105, 122-124, 127, 131, 132, 135-137, 141, 144, 145, 147, 149-151, 186]. Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth), Haida and Inuit are also reported to have consumed northern fur seal [10, 54, 143]. It is reported that northern and central Nootka did not traditionally hunt northern fur seal, but began to do so with the establishment of the European fur trade [122]. Nootka of Vancouver Island did not usually hunt northern fur seal, but caught the mammal should it be found injured or close to shore [151]. Inuit used fur seal as an important source of subsistence during winter, but also consumed it the rest of the year according to availability [54, 143].

Northern fur seal was usually hunted in late winter or spring on-shore or off-shore using harpoon, bow and arrow or club [68, 105, 123, 144]. Offshore, kayaks or canoes were used with a harpoon or bow and arrow [123, 131, 141, 144, 147, 186]. The Makah hunted from canoes in teams of three or four using harpoons with a double shaft and floats [186]. Nootka hunted on open water from canoes in teams of two using harpoons and clubs or shotguns [122]. The Tlingit used a toggling harpoon or a harpoon with a detachable barbed head [135, 136, 144]. Northern fur seal was also hunted on shore or on rocks with clubs [131, 141, 147, 149]. Tlingit used a club and a seal skin disguise as a decoy when hunting or finding wounded animals on shore [149]. Inuit caught northern fur seals at breathing holes with harpoons and nets [54, 143].

Northern fur seal was an important food source for Washington coast cultures. The Makah preferred the taste of northern fur seal to other seal species [46, 186]. The Southeast Alaskan cultures on the other hand, preferred harbour seals to northern fur seal. Some consumed northern fur seal flesh smoked and dipped in oil [132]. The flesh was consumed usually raw and sometimes cooked by the Inuit and the blubber served as a source of fuel [54, 143]. The Nootka boiled the flesh in a wooden vessel of water, into which hot stones were placed [54]. The Makah and Southeast Alaskan cultures are reported to have also consumed the oil [132, 186].

The Tlingit extracted oil from the blubber, traded the oil and skin, and used the bladder to store grease or oil [135, 136, 144]. The Quileute traded the blubber for oysters, sockeye salmon, and eulachon grease from neighbouring cultures [137]. The Haida traded the pelts with the Tsimshian [1].

North Pacific Coast cultures considered northern fur seal hunting to be difficult and believed it could only be achieved by hunters who were talented and who had the favour of the spirits [147]. Northern fur seals later became an internationally protected species and was no longer available to hunt [143].

Inuit (including those of Iglulik, Clyde, Cumberland Sound, Ungava Bay, Labrador, Greenland), Innu, Cree, Micmac (Mi'kmaq), Thule and Beothuk are reported to have consumed harp seal [30, 53, 58, 68, 74, 91, 110, 121, 125, 143, 156, 161, 165, 169, 170, 172, 175-177, 187]. Inuit of Grise Fiord did not consume harp seal, but are reported to have used it for dog food [157]. Beothuk and Inuit of Greenland (Nordost Bay) reportedly considered harp seal an important food source [68, 161, 176]. Inuit of Hopedale, Labrador, considered harp seal the most important of seal species [125] and often stored it for later use [170].

Hunting

Harp seal was hunted and consumed at different times according to region. It was available to Clyde Inuit when the water was open (August), to Ungava Bay Inuit in July, October and November and to Labrador Inuit, Innu and Cree during migration in spring and fall. Thule and Cumberland Sound Inuit hunted in summer. In the Beothuk region, harp seal was available January to May [176]. Micmac of Newfoundland consumed harp seal August to September, and also in January [30, 58, 110, 121, 125, 143, 156, 169, 170, 172, 177, 187]. Inuit of Nordost Bay hunted from kayaks July to October (principally July and August), and hunted on ice until March/April [68] [110].

Harp seal was hunted on open waters (usually from kayaks), from ice or floe edges, and on ice according to region and season [68, 110, 188]. Inugsuk culture reportedly hunted them from kayaks [68]. Labrador Inuit hunted them during fall from kayaks on open waters and hunted them in the winter (mainly after mid-January) at their breathing holes [58]. In winter, West Greenlanders hunted on the ice and at floe edges and sought out breathing holes. They used specialized harpoons and in later times used “kayak harpoons”. Hunters put skins on their feet to silence their steps. On ice in winter, they also practiced a type of cooperative hunting technique called “peep” hunting, where one of the hunters would attract the harp seal, and the other would kill it. In spring and summer they took to the open waters. When kayaking, West Greenlanders used a specialized harpoon with a detachable, barbed head or an unbarbed lance with a fixed head. Sometimes, they used nets. In later times, they used rifles. In spring, they also harpooned harp seal that basking in the sun [161, 188].

Preparation

Harp seal flesh was consumed boiled, fermented, dried and raw (either fresh or frozen) [53, 74, 143, 161].

Uses other than food

Harp seal oil, blubber and byproducts were also used. Greenland and Labrador Inuit used the blubber as a source of fuel and as an item of trade [74, 143]. Sometimes the oil was used as a laxative [74]. Labrador Inuit used harp seal skin to make kayak covers, clothing, and tents [121].

Inuit (including Central – Iglulik – and those of Labrador and Greenland), Beothuk and Inugsuk culture are reported to have eaten hooded seal [68, 74, 91, 110, 121, 143, 161, 176, 188]. Hooded seal is reported to have been one of the Nordost Bay Inuit’s most important food sources [68].

Hooded seal was available at different times in different regions. It was available from January to May in the Beothuk region [176], began to be available in May in the Labrador Inuit region [121], and was not available to Inuit in winter [143].

Cultures hunted on open waters (usually from kayaks), from ice or floe edges and on ice according to region and season [68, 110, 188]. Inugsuk hunted from kayaks [68]. Inuit of Nordost Bay hunted in kayaks July to October (mostly in July and August) and on ice until April [110] [68]. Greenland Inuit hunted from kayaks, ice or floe edges [188]. In the southern area of west Greenland, hooded seal was mainly hunted from May to August. People living on the northern part of west Greenland hunted on the ice, at the floe edge and at breathing holes in winter using specialized harpoons; in summer they used kayaks on open water. When kayaking, the West Greenlanders used specialized harpoons with a detachable, barbed head or lances with a fixed head (and unbarbed), and used throwing boards to throw the harpoons. Sometimes, they used nets. In later times, they used rifles. In spring, they also harpooned hooded seal basking in the sun [161].

The flesh was consumed boiled, fermented, dried and raw (fresh or frozen) [74, 143, 161]. Most Inuit consumed hooded seal raw, but some were known to cook it [143]. West Greenlanders boiled the fresh flesh, but often froze the raw flesh for later use, at which point it was consumed raw frozen. Sometimes, they dried the raw flesh for later use [161].

Greenland and Labrador Inuit also consumed the liver, kidney and heart. The liver was usually consumed raw and was a children’s favourite. They often prepared hooded seal broth and consumed it as a hot beverage. Greenland and Labrador Inuit consumed hooded seal blood in a blood soup [74]. West Greenlanders distributed small strips of skin and blubber to children [161].

Greenland and Labrador Inuit used the blubber as a source of fuel and as a trade item and sometimes used the oil as a laxative [74, 143].

Inuit (including Central Inuit of Northern Hudson Bay), Yupik of Southwest Alaska and Inupiat of Northwest Alaska (including those of Point Barrow) are reported to have consumed ribbon seal [68, 91, 99, 143, 166, 167], however Central Inuit and some Alaskan cultures rarely consumed it due to limited availability [68, 91, 166, 167].

Ribbon seal was an important food source during winter, but it was also used throughout the year. Nets and harpoons were used in winter at breathing holes [143]. Point Barrow Inupiat hunted caught ribbon seal only if encountered while hunting other seal species at night with nets [166].

Ribbon seal flesh was consumed raw or cooked. Inuit ate it raw most of the time, stored the flesh frozen for later use and used the oil as a fuel source [143].

Labrador Inuit (from Hopedale and Makkovik), Beothuk and Wampanoag are reported to have consumed gray seal [125, 165, 176, 183]. In more recent times, the Wampanoag stopped consuming it because it was no longer available in their region [183]. The Beothuk are thought to have hunted gray seal from July to April, the season when they were available [176].

References

1. Government of British Columbia: British Columbia Heritage Series: Our Native Peoples. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1952.

2. Government of British Columbia: Vol 1: Introduction to our Native Peoples. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1966.

3. Thommesen H: Telling Time With Shadows: The Old Indian Ways. In: Bella Coola Man: More Stories of Clayton Mack. edn. Edited by Thommasen H. Madeira Park, B.C: Harbour Publishing; 1994: 24-45.

4. Ackerman RE: Prehistory of the Asian Eskimo Zone. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 106-118.

5. Ashwell R: Food, Fishing & Hunting; Cooking Methods. In: Coast Salish: Their Art, Culture and Legends. Volume 1st edition, edn. British Columbia: Hancock House Publishers Inc.; 1978: 28-55.

6. Bancroft HH: The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America. New York: D. Appleton; 1875.

7. Barnett HG: Food; Occupations. In: The Coast Salish of British Columbia. Volume 1st edition, edn. Eugene: University of Oregon; 1955: 59-107.

8. Batdorf C: Northwest Native Harvest. Surrey, B.C: Hancock House Publishers Ltd.; 1990.

9. Berkes F, Farkas CS: Eastern James Bay Cree Indians: Changing Patterns of Wild Food Use and Nutrition. In.; 1978.

10. Blackman MB: Haida: Traditional Culture. In: The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute; 1990: 240-245.

11. Boas F: Kwakiutl Ethnography. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1966.

12. Boas F: The Eskimo of Baffin Land and Hudson Bay: from notes collected by Capt. George Comer, Capt. James S. Mutch, and Rev. E. J. Peck, vol. reprinted from the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, v. 15, pt. 1, published in 1901 and v.15, pt. 2, 1907. New York: AMS Press Inc.; 1975.

13. Bock PK: Micmac. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 109-122.

14. D'Anglure BS: Inuit of Quebec. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 477-498.

15. Damas D: Environment, History, and Central Eskimo Society. In: Cultural Ecology: Readings on the Canadian Indians and Eskimos. edn. Edited by Cox B. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited; 1973: 269-300.

16. Davis SD: Prehistory of Southeastern Alaska. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 197-202.

17. Damas D: Central Eskimo: Introduction. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 391-396.

18. de Laguna F: Eyak. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 189-191.

19. Densmore F: Nootka and Quileute Music. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office; 1939.

20. Dumond DE: Prehistory of the Bering Sea Region. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 94-105.

21. Fitzhugh WW: Paleo-Eskimo Cultures of Greenland. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 528-538.

22. Freeman MMR: Tradition and Change: Problems and Persistence in the Inuit Diet. In: Coping with Uncertainty in Food Supply. edn. Edited by de Garine I, Harrison GA. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1988: 150-169.

23. Ho KJ, Mikkelson B, Lewis LA, Feldman SA, Taylor CB: Alaskan Arctic Eskimo: Responses to a Customary High Fat Diet. Am J Clin Nutr 1972, 25:737-745.

24. Honigmann JJ: Foodways in a Muskeg Community: An Anthropological Report on the Attawapiskat Indians. Ottawa: Northern Co-ordination and Research Centre, Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources; 1948.

25. Honigmann JJ: West Main Cree. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 217-222.

26. Jewitt JR: Captive of The Nootka Indians: The Northwest Coast Adventure of John R. Jewitt, 1802-1806. Boston: Back Bay Books; Distributed by Northeastern University Press; 1993.

27. Krause A: The Tlingit Indians: Results of a Trip to the Northwest Coast of America and the Bering Straits. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1956.

28. Kuhnlein HV: Traditional and Contemporary Nuxalk Foods. Nutrition Research 1984, 4:789-809.

29. Lantis M: Nunivak Eskimo. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 209-221.

30. Mackey MGA: Nutrition: Does Access to Country Food Really Matter? In.; 1987.

31. Matthiasson JS: Living on the Land: Change among the Inuit of Baffin Island. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press Ltd.; 1992.

32. Maxwell MS: Pre-Dorset and Dorset Prehistory of Canada. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 359-366.

33. McGhee R: Beluga Hunters: An archaelogical reconstruction of the history and culture of the Mackenzie Delta Kittegaryumiut, vol. Series: Newfoundland Social and Economic Studies No.13. St. John's: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland; 1974.

34. McGhee R: Thule Prehistory of Canada. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 269-376.

35. McGhee R: Disease and the Development of Inuit Culture. In.; 1994.

36. McIlwraith TF: The Bella Coola Indians. Toronto: University of Toronto; 1948.

37. Mitchell D: Prehistory of the Coasts of Southern British Columbia and Northern Washington. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 340-358.

38. Murdock GP: The Haida of British Columbia : Our Primitive Contemporaries. New York: MacMillan Co.; 1963.

39. Nicolaysen R: Arctic Nutrition. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 1980:295-310.

40. Nobmann ED, Mamleeva FY, Klachkova EV: A Comparison of the Diets of Siberian Chukotka and Alaska Native Adults and Recommendations for Improved Nutrition, a Survey of Selected Previous Studies. Arct Med Res 1994, 53:123-129.

41. Petersen R: East Greenland before 1950. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute; 1984: 622-631.

42. Preston RJ: East Main Cree. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 196-207.

43. Prins HEL: The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival, vol. Series: Case studies in Cultural Anthropology. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996.

44. Reynolds B: Beothuk. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 101-108.

45. Zenk HB: Siuslawans and Coosans. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles WP. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Insitution; 1990: 572-573.

46. Wessen G: Prehistory of the Ocean Coast of Washington. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 412-419.

47. The Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program Staff: Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Handbook - A Practical Guide to Family Foods and Nutrition Using Native Foods; 1984.

48. Rogers ES: Subsistence Areas of the Cree-Ojibwa of the Eastern Subarctic: A Preliminary Study. Contributions of Ethnology V 1967, No. 204:59-90.

49. Rogers ES, Smith JGE: Environment and Culture in the Shield and Mackenzie Borderlands. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 131-137.

50. Seaburg WR, Miller J: Tillamook. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles WP. Washington: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 560-566.

51. Silverstein M: Chinookans of the Lower Columbia. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 533-536.

52. Speck FG: Animals in Special Relation to Man. In: Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Volume New edition, edn. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1977: 72-127.

53. Speck FG, Dexter RW: Utilization of animals and plants by the Micmac Indians of New Brunswick. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 1951, 41(8):250-259.

54. Sproat GM: The Nootka: Scenes and Studies of Savage Life, vol. West Coast Heritage Series. Victoria, B.C.: Sono Nis Press; 1987.

55. Stewart FL: The Seasonal Availability of Fish Species Used by the Coast Tsimshians of Northern British Columbia. Syesis 1975, 8:375-388.

56. Suttles W: Coping with abundance: subsistence on the Northwest Coast. In: Man the hunter. edn. Edited by Lee RB, DeVore I. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1968: 56-68.

57. Suttles W: Coast Salish Essays, vol. 1st edition. Seattle: University of Washingtion Press; 1987.

58. Taylor JG: Historical Ethnography of the Labrador Coast. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 508-518.

59. Verdier PC, Eaton RDP: A study of the nutritional status of an Inuit population in the Canadian high arctic. Part 2. Some dietary sources of vitamins A and C. Canadian Journal of Public Health 1987, 78(4):236-239.