Porpoises General

Hunting

Porpoise was reported to be hunted spring through summer by the Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth) [6], Inuit [23], Micmac (Mi’kmaq) [2] and Eastern Abenaki [21].

Porpoise was hunted on open waters in smooth, quiet canoes to avoid noise on approach. Weapons included harpoons, clubs and spears [41]. Harpoons were often shafts made of antler and points made of mussel shells, bone or antler [42]. The Coast Salish hunted in teams of three using single-pronged harpoons with a trident end [13, 14, 16]. The Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka’wakw) used a two-pronged harpoon with a detachable head [38, 40]. Cultures on Vancouver Island used double-pronged harpoons, with one of the prongs twice as long as the other [30]. The Tlingit used barbed and tanged points made of bone, antler, copper or iron attached to a wooden shaft [9, 11]. The harpoons used by West Greenlanders were made of wood, antler or bone, with a knob of ivory and a removable head made of iron. They also used lances [24]. The Micmac of Richibucto used harpoons made of bone or walrus ivory [3].

In order to attract porpoise, the Northern and Central Nootka [19], Southern Kwakiutl [31] and Nuxalk [31] used sand or fine gravel thrown on water, which looked like small fish eating on the water’s surface. The people of Puget Sound [30], Southern Kwakiutl [31] and Nuxalk [31] are reported to have hunted porpoise at night. Occasionally, the Micmac of Richibucto collected porpoise stranded on the beach [3].

For the Coast Salish, the porpoise hunt was reserved for members of higher status, determined by the productivity of a man and his ability to share food with others [13, 16, 17].

Preparation

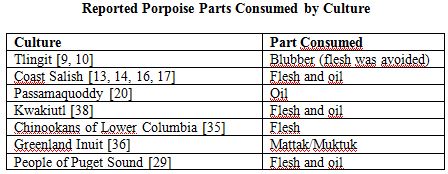

Different cultures had preferences regarding porpoise parts consumed.

Penobscot are reported to have consumed porpoise flesh on occasion, but they found it too greasy to eat on a regular basis [28]. Although the Tlingit consumed porpoise on occasion, they are reported to have usually avoided the meat, associating it with poverty and claiming that consuming it produced a foul body smell and nasal blood losses [9, 10]. In contrast, the Coast Salish and other coastal peoples considered porpoise a delicacy [13, 17, 43].

The Penobscot braised porpoise meat cut in slices [28]. The people of Puget Sound consumed the meat either raw or cooked (poached, roasted on ashes or spits, baked, or stewed) [29]. The Coast Salish [14], Kwakiutl [39] and Tlingit [10] boiled the meat in vessels filled with water into which they tossed hot stones. The Coast Salish vessel was a cedar box or an emptied canoe. They also recovered the oil from boiled meat or blubber in wooden vessels; this oil was then used as a dip for dried meat and salmon [14, 17].

Uses other than food

Porpoise oil had an important trading value: the Micmac [1] and the people from Puget Sound [29] used it in trades.

Beliefs and taboos

The Coast Salish porpoise hunt was preceded by rituals such as bathing and religious ceremonies [13]. They would invoke the killer whale spirit by means of a ritual song unique to an individual hunter [14]. When men were out hunting, their wives were required to remain silent and refrain from combing their hair [14].

Cultures on the British Columbian coast, including the Northern Coast Salish and Tlingit, are reported to have consumed harbor porpoise [45, 46]. The Tlingit are reported to have hunted and consumed ‘white porpoise’ [11], which may be a reference to harbor porpoise. The Salish worked in pairs of dedicated hunters using canoes and harpoons with trident ends and removable heads. Floats attached with a long line were used to distinguish hunters [45]. Some cultures reserved the best parts of the catch (namely the chest meat) for people of higher rank [46].

The Nuxalk are reported to have occasionally used Dall’s porpoise as a source of food [47]. The Tlingit are reported to have hunted and consumed ‘big porpoise’ [11], which may refer to Dall’s porpoise.

References

1. Bock PK: Micmac. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 109-122.

2. Stoddard NB: Micmac Foods, vol. re-printed from the Journal of Education February 1966. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Halifax Natural Science Museum; 1970.

3. Speck FG, Dexter RW: Utilization of animals and plants by the Micmac Indians of New Brunswick. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 1951, 41(8):250-259.

4. Vanstone JW: Athapaskan Adaptations: Hunters and Fishermen of the Subarctic Forests. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1974.

5. Jewitt JR: Captive of The Nootka Indians: The Northwest Coast Adventure of John R. Jewitt, 1802-1806. Boston: Back Bay Books; Distributed by Northeastern University Press; 1993.

6. Ruddell R: Chiefs and Commoners: Nature's Balance and the Good Life Among the Nootka. In: Cultural Ecology: Readings on the Canadian Indians and Eskimos. edn. Edited by Cox B. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart; 1973: 254-265.

7. Mitchell D: Prehistory of the Coasts of Southern British Columbia and Northern Washington. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 340-358.

8. Arima E, Dewhirst J: Nootkans of Vancouver Island. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 391-397.

9. de Laguna F: Tlingit. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 203-212.

10. Emmons GT: Food and Its preparation. In: The Tlingit Indians. edn. Edited by de Laguna F. New York: American Museum of Natural History; 1991: 140-153.

11. Oberg K: The Annual Cycle of Production. In: The Social Economy of the Tlingit Indians. edn.: University of Washington Press; 1973: 65.

12. Speck FG, Dexter RW: Utilization of marine life by the Wampanoag Indians of Massachusetts. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 1948, 38(8):257-265.

13. Ashwell R: Food, Fishing & Hunting; Cooking Methods. In: Coast Salish: Their Art, Culture and Legends. Volume 1st edition, edn. British Columbia: Hancock House Publishers Inc.; 1978: 28-55.

14. Barnett HG: Food; Occupations. In: The Coast Salish of British Columbia. Volume 1st edition, edn. Eugene: University of Oregon; 1955: 59-107.

15. Batdorf C: Northwest Native Harvest. Surrey, B.C: Hancock House Publishers Ltd.; 1990.

16. Suttles W: Coast Salish Essays, vol. 1st edition. Seattle: University of Washingtion Press; 1987.

17. Government of British Columbia: Vol 1: Introduction to our Native Peoples. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1966.

18. Suttles W: Central Coast Salish. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 453-460.

19. Drucker P: The Northern and Central Nootkan tribes. Washington,D.C.: Government Printing Office; 1951.

20. Erickson VO: Maliseet-Passamaquoddy. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 123-136.

21. Snow DR: Eastern Abenaki. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 137-139.

22. McCartney AP: Prehistory of the Aleutian Region. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 119-135.

23. Clark DW: Pacific Eskimo: Historical Ethnography. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington: Smithsonian Institute; 1984: 189-191.

24. Kleivan I: West Greenland Before 1950. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 595-609.

25. Davis SD: Prehistory of Southeastern Alaska. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 197-202.

26. Hilton SF: Haihais, Bella Bella, and Oowekeeno. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 312-316.

27. Government of British Columbia: British Columbia Heritage Series: Our Native Peoples. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1952.

28. Speck FG. In: Penobscot Man The Life History of a Forest Tribe in Maine. edn. USA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1940.

29. Eells M: The Indians of Puget Sound: The Notebooks of Myron Eells. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1985.

30. Waterman TT: Hunting Implements, Nets and Traps. In: Inidan Notes and Monographs No 59 Notes on the Ethonology of the Indians of Puget Sound. edn. New York. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation.: J.J. Augustin, Gluckstadt, Germany.; 1973.

31. Kirk R: Daily Life. In: Wisdom of the Elders: Native Traditions on the Northwest Coast- The Nuu-chah-nulth, Southern Kwakiutl and Nuxalk. edn. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre in association with The British Columbia Provincial Museum; 1986: 105-138.

32. Wessen G: Prehistory of the Ocean Coast of Washington. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 412-419.

33. Powell JV: Quileute. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 431-432.

34. Hajda Y: Southwestern Coast Salish. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 503-507.

35. Silverstein M: Chinookans of the Lower Columbia. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 533-536.

36. Nicolaysen R: Arctic Nutrition. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 1980:295-310.

37. Hill-Tout C: Food and Cooking. In: British North America: The Far West, the Home of the Salish and Dene. edn. Edited by Hill-Tout C. London: Archibald Constable; 1907: 89-108.

38. Government of British Columbia: Vol 7: Kwakiutl. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1966.

39. Boas F: Kwakiutl Culture as Reflected in Mythology. New York: G.E. Stechert & Co.; 1935.

40. Goddard PE. In: Indians of the Northwest Coast. edn. New York: American Museum of Natural History; 1924.

41. Drucker P: Indians of the Northwest Coast. New York: The natural History Press; 1955.

42. Newcomb WW: North American Indians: An Anthropological Perspective. Pacific Palisades, California: Goodyear Publishing Company, Inc.; 1974.

43. Drucker P: Cultures of the North Pacific Coast. Scranton, Pennsylvania: Chandler Publishing Company; 1965.

44. Speck FG: Animals in Special Relation to Man. In: Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Volume New edition, edn. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1977: 72-127.

45. Kennedy DID, Bouchard RT: Northern Coast Salish. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: 1990; 1990: 441-445.

46. Stephenson PH, Elliot SJ, Foster LT, Harris J: A persistent spirit: towards understanding Aboriginal health in British Columbia. In. Edited by Stephenson PH, Elliot SJ, Foster LT, Harris J, vol. 1. Victoria: Department of Geography, University of Victoria; 1995.

47. Kuhnlein HV: Traditional and Contemporary Nuxalk Foods. Nutrition Research 1984, 4:789-809.