Otters General

Cultures consumed otter as a primary food source or when other sources of food were scarce. Otter was also hunted for its fur. Cultures that consumed it in times of scarcity include the Han [25], the Kutchin (Gwich’in) from Peel and Crow River [41] and Attawapiskat Cree [7]. Others, such as the Round Lake Ojibwa (Anishinabek) [7] fed otter to the dogs rather than consuming it.

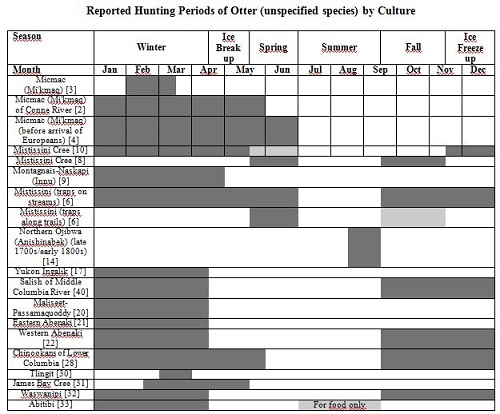

Otter was hunted throughout the year according to the periods described in the following table (relation between seasons and calendar months are approximate and changes according to location – darker color is the reported preferred period). Hunting season was primarily during fall, winter or spring, when the fur was thick and usable for clothing.

The otter hunters used traps (deadfalls, snares), bows and arrows and spears. The Puget Sound culture [42] used two-pronged spears. The Salish [40] and the Spokane [18] used snares and other traps placed along animal tracks. The Salish [40] baited the traps with shellfish. The Spokane [18] avoided setting traps close to springs or salt licks. Yukon Ingalik [17] used deadfalls or tether snares along with bows and arrows. The Tlingit [30] used deadfalls. The Athapaskan of Arctic Drainage Lowlands [37] used deadfalls, bow and arrows and nets. They also destroyed otter dens on occasion. The Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw) [38] used noose traps. The Mistissini Cree used deadfalls, bows and arrows and nets. More recently, the Mistissini Cree hunted otter with steel traps and rifles [6, 8, 9]. The Western Abenaki [22], James Bay Cree [31], Abitibi [33], Hopedale Inuit [39] and Micmac (Mi'kmaq) [2] used traps. The Micmac used toboggans and snowshoes to access their traps and bring back their catch; more recently they used skidoos [2]. For the Mistissini Cree [10] and the Coastal Montagnais (Innu) [36], hunting was carried out by men, however anyone in the Abitibi community physically capable participated in otter trapping [33].

The Mistissini Cree hung otter in the house, allowing it to thaw before preparing it. They prepared a special meal when the first otter of the season was caught. They shared the otter meat, but the hunter kept the fur [8-10]. The Attawapiskat Cree used otter fat and the foetus when other food sources were scarce [12]. The Micmac boiled otter in a wood or bark vessel. They also roasted or grilled the flesh and preserved meat for winter by smoking or drying [1, 3, 4].

Although otter was used for food, it was primarily hunted for its fur, which was valuable and used for trade with Europeans. Cultures that traded otter fur include the Coeur d’Alene [19], Tlingit [30], Vunta Kutchin [35], Peel and Crow River Kutchin [41], Athapaskan from Arctic Drainage Lowlands [37], Inuit [43], Chipewyan [15], Mistissini Cree [9-11], James Bay Cree [24, 31], Micmac [1, 2], Maliseet-Passamaquoddy [20], Abenaki [21, 22] and Abitibi [33].

Otter paws were believed to hold some power. The Coastal Montagnais [36] kept otter paws to satisfy the animal’s spirit. The Abitibi [33] checked their luck by throwing otter front paws in the air; it was believed that if they landed with palms up, it was a sign of good fortune.

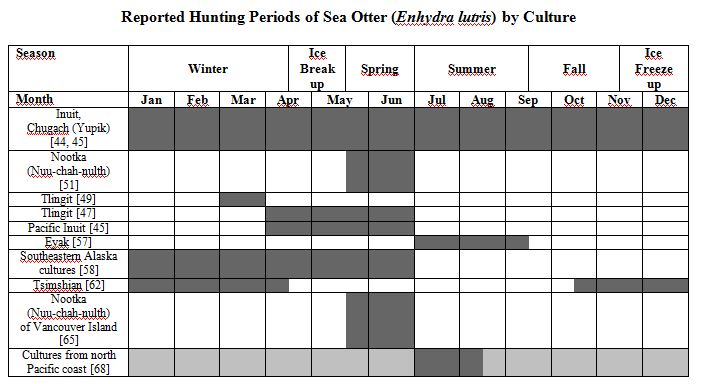

Sea otter was hunted throughout the year according to the periods described in the following table (relation between seasons and calendar months are approximate and changes according to location – darker color is the reported preferred period).

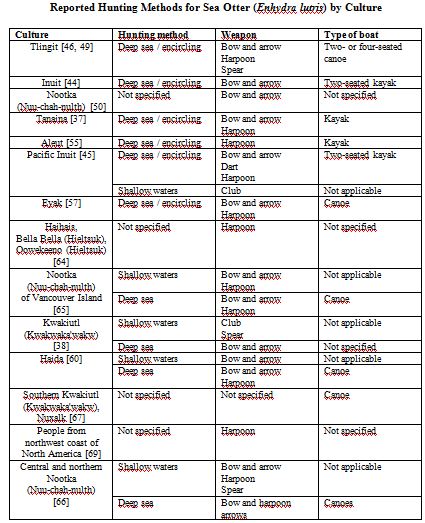

Two main hunting methods were practiced. The most common was to hunt on open waters in teams, using canoes or kayaks, encircling the sea otter and killing it with spears, harpoons or bows and arrows. The other method was to use clubs or spears on a sleeping sea otter in shallow water.

The arrow used by the Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw) [38] had a detachable head attached with a line ending with a feather that was used as a marker. The harpoon used by the Haida [60] for deep sea hunting was made of a cedar shaft and bone head. Other cultures from the northwest coast [69] made the head using mussel shells or antler. More recently, the Tlingit [48] and the Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth) [50] used rifles to hunt sea otter. In the central and northern Nootka [66], the canoe teams were composed of a marksman and a steersman, usually from the same family. Older men usually occupied the role of steersman.

Cultures that boiled sea otter include the Puget Sound [34], Nootka [50], Tlingit [48] and Eyak [56]; hot rocks were added to a vessel containing water [34, 48, 68]. The Coast Salish [53] consumed sea otter as part of a stew or a soup. The Puget Sound culture [34] also grilled sea otter. Besides poaching sea otter meat, the Eyak [56] used blood in soups and dried the meat. They sometimes cooked sea mammals with land mammals, but rarely because they considered that it spoiled the flavor of the broth. Cultures from the north Pacific coast [68], who considered sea otter as a delicacy, also grilled or steamed it.

Sea otter fur was a highly valued pelt of the European and Indigenous traders [34, 38, 46]. The Tlingit [46-48], the Nootka [50], the Coast Salish [52], the Kwakiutl [38], the Haida [61], and the central and northern Nootka [66] traded sea otter furs.

The Tsimshian sea otter hunt was practiced only by men [62]. They practiced a purification ritual before hunting, where they fasted, bathed, drank purifying juices, and refrained from sexual activity. For the Eyak [56], sea otter meat was taboo for menstruating or pregnant women.

After the arrival of Europeans, the sea otter population drastically diminished. Local extinctions were reported as early as the 1800s [69]. Fur trade [69] and the use of rifles [48] were two factors that are thought to have contributed to the species’ decline. To face the challenge of reduced sea otter populations, the Nootka of Vancouver Island [65] and the central and northern Nootka [66] transitioned from the shallow water method to the deep sea method. Measures were soon taken to prevent the complete disappearance of sea otter. In the early 1910s, a treaty between Russia, USA, Japan, and UK (which included Canada) prohibited the hunting of sea otter [55].

The Pacific Inuit [45], the Oowekeeno (Hieltsuk) [64] and the Micmac (Mi'kmaq) of Richibucto [70] are reported to have consumed river otter. The Coast Salish [53], the prehistoric cultures of southeastern Alaska [58] and the Southwestern Coast Salish of Quinault highlands [54] also consumed river otter. The Tlingit [46] are reported to have consumed river otter as a minor source of food. It is believed that the prehistoric cultures of southeastern Alaska [58] hunted during winter. The Coast Salish [53] cooked river otter in a stew or a soup, using hot stones as source of heat. The Omushkego Cree [71] hunted river otter, but did not usually consume it. The Micmac [70] and Omushkego Cree hunted during fall and spring. The Omushkego Cree traded river otter fur. The Micmac are reported to have used deadfalls and snares [70].

References

1. Bock PK: Micmac. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 109-122.

2. Mackey MGA, Bernard L, Smith BS: The Micmacs of Conne River Newfoundland - A Qualitative and Quantitative Study of Food: Its Procurement and Use. In.

3. Stoddard NB: Micmac Foods, vol. re-printed from the Journal of Education February 1966. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Halifax Natural Science Museum; 1970.

4. Prins HEL: The Mi'kmaq: Resistance, Accommodation, and Cultural Survival, vol. Series: Case studies in Cultural Anthropology. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996.

5. Meyer D: Appendix I: Plants, Animals and Climate; Appendix IV: Subsistence-Settlement Patterns. In: The Red Earth Crees, 1860-1960. Volume 1st edition, edn.: National Musem of Man Mercury Series; 1985: 175-185-200-223.

6. Rogers ES: Equipment for Securing Native Foods and Furs. In: The Material Culture of the Mistassini. edn.: National Museum of Canada, Bulletin 218; 1967: 67-88.

7. Rogers ES: Subsistence Areas of the Cree-Ojibwa of the Eastern Subarctic: A Preliminary Study. Contributions of Ethnology V 1967, No. 204:59-90.

8. Rogers ES: The Quest for Food and Furs: The Mistassini Cree, 1953-1954. Ottawa: Museums of Canada; 1973.

9. Rogers ES, Leacock E: Montagnais-Naskapi. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 169-189.

10. Tanner A: Bringing Home Animals: Religious Ideology and Mode of Production of the Mistassini Cree Hunters, vol. 1st edition. London: C. Hurst & Company; 1979.

11. Rogers ES: Subsistence. In: The Hunting Group-Hunting Territory Complex among the Mistassini Indians. edn. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada Bulletin No. 195; 1963: 32-53.

12. Honigmann JJ: Foodways in a Muskeg Community: An Anthropological Report on the Attawapiskat Indians. Ottawa: Northern Co-ordination and Research Centre, Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources; 1948.

13. Preston RJ: East Main Cree. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 196-207.

14. Rogers ES, Taylor JG: Northern Ojibwa. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 231-235.

15. Smith JGE: Chipewyan. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 271-277.

16. McFadyen Clark A: Koyukon. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 582-590.

17. Snow JH: Ingalik. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 6: Subarctic. edn. Edited by Helm J. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981: 602-607.

18. Ross JA: Spokane. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 12: Plateau. edn. Edited by Walker DE, Jr. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1998: 271-282.

19. Palmer G: Coeur d'Alene. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 12: Plateau. edn. Edited by Walker DE, Jr. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1998: 313-318.

20. Erickson VO: Maliseet-Passamaquoddy. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 123-136.

21. Snow DR: Eastern Abenaki. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 137-139.

22. Day GM: Western Abenaki. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15: Northeast. edn. Edited by Trigger BG. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1978: 148-156.

23. Mandelbaum DG: The Plains Cree: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Comparative Study, vol. 1st edition. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center; 1979.

24. Berkes F, Farkas CS: Eastern James Bay Cree Indians: Changing Patterns of Wild Food Use and Nutrition. In.; 1978.

25. Osgood C: The Han Indians: A Compilation of Ethnographic and Historical Data on the Alaska-Yukon Boundary Area, vol. Yale University Publications in Anthropology Number 74. New Haven: Department of Anthropology Yale University; 1971.

26. Burch ES, Jr.: Kotzebue Sound Eskimo. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1984: 303-311.

27. Kennedy DID, Bouchard RT: Northern Coast Salish. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: 1990; 1990: 441-445.

28. Silverstein M: Chinookans of the Lower Columbia. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 533-536.

29. Bauer G: Fort George Cookbook; 1967.

30. Oberg K: The Annual Cycle of Production. In: The Social Economy of the Tlingit Indians. edn.: University of Washington Press; 1973: 65.

31. Elberg N, Hyman J, Hyman K, Salisbury RF: Not By Bread Alone: The Use of Subsistence Resources among James Bay Cree. In.; 1975.

32. Feit HA: Waswanipi Realities and Adaptations: Resource Management and Cognitive Structure. In.; 1978.

33. Jenkins WH: Notes on the hunting economy of the Abitibi Indians. In., vol. 9. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America; 1939.

34. Eells M: The Indians of Puget Sound: The Notebooks of Myron Eells. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1985.

35. Balikci A: Game Distribution. In: Vunta Kutchin Social Change A Study of the People of Old Crow, Yukon Territory. edn. Ottawa: Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources; 1963.

36. Speck FG: Animals in Special Relation to Man. In: Naskapi: The Savage Hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Volume New edition, edn. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1977: 72-127.

37. Vanstone JW: Athapaskan Adaptations: Hunters and Fishermen of the Subarctic Forests. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1974.

38. Government of British Columbia: Vol 7: Kwakiutl. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1966.

39. Labrador Inuit Association: Our Footprints Are Everywhere: Inuit Land Use and Occupancy in Labrador. Nain: Labrador Inuit Association; 1977.

40. Miller J: Middle Columbia River Salishans. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 12: Plateau. edn. Edited by Walker DE, Jr. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1998: 253-270.

41. Osgood C: Material Culture: Food. In: Contributions to the Ethnography of the Kutchin. edn. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1936: 23-39.

42. Waterman TT: Hunting Implements, Nets and Traps. In: Inidan Notes and Monographs No 59 Notes on the Ethonology of the Indians of Puget Sound. edn. New York. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation.: J.J. Augustin, Gluckstadt, Germany.; 1973.

43. Thiry P, Thiry M: Eskimo Artifacts Designed for Use. In: Eskimo Artifacts Designed for Use. edn. Seattle, Washington: Superior Publishing Company; 1977.

44. Birket-Smith K: The Struggle For Food. In: Eskimos. edn. Rhodos: The Greenland Society with the support of The Carlsberg Foundation and The Ministry for Greenland; 1971: 75-113.

45. Clark DW: Pacific Eskimo: Historical Ethnography. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Edited by Damas D. Washington: Smithsonian Institute; 1984: 189-191.

46. de Laguna F: The Story of a Tlingit Community: A Problem in the Relationship between Archeological, Ethnological, and Historical Methods. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office; 1960.

47. de Laguna F: Tlingit. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 203-212.

48. Krause A: The Tlingit Indians: Results of a Trip to the Northwest Coast of America and the Bering Straits. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1956.

49. Oberg K: The Social Economy of the Tlingit Indians. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press; 1973.

50. Jewitt JR: Captive of The Nootka Indians: The Northwest Coast Adventure of John R. Jewitt, 1802-1806. Boston: Back Bay Books; Distributed by Northeastern University Press; 1993.

51. Ruddell R: Chiefs and Commoners: Nature's Balance and the Good Life Among the Nootka. In: Cultural Ecology: Readings on the Canadian Indians and Eskimos. edn. Edited by Cox B. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart; 1973: 254-265.

52. Ashwell R: Food, Fishing & Hunting; Cooking Methods. In: Coast Salish: Their Art, Culture and Legends. Volume 1st edition, edn. British Columbia: Hancock House Publishers Inc.; 1978: 28-55.

53. Batdorf C: Northwest Native Harvest. Surrey, B.C: Hancock House Publishers Ltd.; 1990.

54. Hajda Y: Southwestern Coast Salish. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 503-507.

55. Lantis M: Aleut. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 5: Arctic. edn. Washington, DC; 1984: 161-183.

56. Birket-Smith K, DeLaguna F. In: The Eyak Indians of the Copper River Delta, Alaska. edn. Kobenhavn: Levin & Munksgaard; 1938.

57. de Laguna F: Eyak. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 189-191.

58. Davis SD: Prehistory of Southeastern Alaska. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 197-202.

59. Blackman MB: Haida: Traditional Culture. In: The Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute; 1990: 240-245.

60. Murdock GP: The Haida of British Columbia : Our Primitive Contemporaries. New York: MacMillan Co.; 1963.

61. Government of British Columbia: British Columbia Heritage Series: Our Native Peoples. Victoria: British Columbia Department of Education; 1952.

62. Halpin MM, Seguin M: Tsimshian Peoples: Southern Tsimshian, Coast Tsimshian, Nishga, and Gitksan. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 267-271.

63. Cox BA. In: Native People, Native Lands. edn. Ottawa: Carleton University Press; 1992.

64. Hilton SF: Haihais, Bella Bella, and Oowekeeno. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 312-316.

65. Arima E, Dewhirst J: Nootkans of Vancouver Island. In: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 7: Northwest Coast. edn. Edited by Suttles W. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1990: 391-397.

66. Drucker P: The Northern and Central Nootkan tribes. Washington,D.C.: Government Printing Office; 1951.

67. Kirk R: Daily Life. In: Wisdom of the Elders: Native Traditions on the Northwest Coast- The Nuu-chah-nulth, Southern Kwakiutl and Nuxalk. edn. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre in association with The British Columbia Provincial Museum; 1986: 105-138.

68. Drucker P: Cultures of the North Pacific Coast. Scranton, Pennsylvania: Chandler Publishing Company; 1965.

69. Newcomb WW: North American Indians: An Anthropological Perspective. Pacific Palisades, California: Goodyear Publishing Company, Inc.; 1974.

70. Speck FG, Dexter RW: Utilization of animals and plants by the Micmac Indians of New Brunswick. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 1951, 41(8):250-259.

71. Berkes F, George PJ, Preston RJ, Hughes.A, Turner J, Cummins BD: Wildlife Harvesting and Sustainable Regional Native Economy in the Hudson and James Bay Lowland, Ontario. Arctic 1994, Vol. 47 No. 4:350-360.

Otters General

Otters are medium-sized mammalian carnivores, either fully aquatic in lifestyle, like the sea otter (Enhydra lutris), or semi-aquatic, like the northern river otter (Lontra canadensis). They are both North American members of the mustelid family, including weasels, American mink (Neovison vison), wolverine (Gulo gulo), and fisher (Martes pennanti).

Like other members of the mustelid family, otter have dense fur, highly prized in the fur industry, long canines, short limbs, and a long, slender body. They have very short, rounded ears and a flattened head. They are at home in water and are excellent swimmers. Otter feed mostly on aquatic prey, like sea urchin, abalone, crab, sea star, octopus, and other mollusks, but also on fish, frogs, and birds [1].

The sea otter (Enhydra lutris) is a fully aquatic mammalian carnivore occurring along the North Pacific Ocean northward from San Francisco to Alaska in a broad range of shallow coastal habitats, from protected bays to exposed outer shores. According to COSEWIC, sea otters are of special concern and are threatened in California, with a North American population of around 75,000 animals. Sea otters are called loutre de mer in French.

Sea otters are the largest member of the weasel family, but the smallest marine mammal, adults typically weighing 27 kg, and unlike most other marine mammals they have no fat blubber.

Sea otters spend the majority of their life at sea, feeding, breeding, resting, and giving birth exclusively at sea. Many individuals can be seen together, resting and interacting while floating in a big “raft” of up to 100 individuals. They dive to feed on marine invertebrates, like clams, crabs, and sea urchins, and are known to use tools, like rocks, to break thick shells. They are often seen floating on their back with food items on their belly and using hard objects to crush open prey shells. Sea otters breed year-round, but individual females first breed after their third year and produce one young per year. They are long-lived and can reach up to 20 years old [1, 2].

The northern river otter (Lontra canadensis) is a semi-aquatic mammalian carnivore occurring in most of Canada and United States, but has been extirpated or is rare in many states. They occupy coastal or freshwater habitats, including large rivers, streams, lakes, and marshes.

Northern river otters are almost half the size of sea otters, and adults typically weigh 8 kg. They are generally solitary and breed once a year producing 2-3 young. Like other weasels, female otters can delay the implantation of the embryo and give birth the following year. They mostly hunt at night and are efficient swimmers, often pursuing prey underwater. They feed mainly on fish, frogs, turtles, birds, and their eggs [1, 2].

References

1. Wilson DE, Ruff S: The Smithsonian book of North American mammals. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 1999.

2. Estes JA, Bodkin J, L.: Otters. In: Encyclopedia of marine mammals. edn. Edited by Perrin WF, Wursig B, Thewissen JGM. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002: 842-858.